When we visited the Royal Ontario Museum this past August, I knew that I could not visit every nook and cranny as much as I might have liked to. I also knew that with five of us having different interests that we were going to get very frustrated very quickly if we stuck together. Upon entering and deciding who wanted to pay extra for the special dinosaur exhibit, I announced the three places that I wanted to focus on and whoever came with would be welcome, but if they wanted to explore on their own and meet back through texts, that would be great.

As an aside, I do miss my little ones, but I really appreciate going on vacation with teenagers and older kids because of this freedom for all of us. I didn’t want to see the dinosaurs; more to the point, I didn’t want to PAY to see them, so I didn’t. My daughter was not a fan of medieval arms and armor and so she veered away from that. The technology of texting let us know where the others were when we were engrossed in our little worlds. It was fantastic! And I think we all benefited from the freedom to explore our interests and the freedom from each other for an hour or so.

My three focuses were in the areas of First Nations, Medieval History and Arms & Armor, and Judaica.

The First Nations section began with a land acknowledgment as well as a First Peoples acknowledgement. Of course, being in Canada, all the displays were bilingual, in English and French. The Museum also acknowledged their six Native advisors from across Canada to choose what items and artifacts to include in the collections and shared their meanings and knowledge.

As I walked around this dedicated space, I recognized many symbols and artifacts. Canada in Ontario and New York are very similar in their Native history. They share common nations, common customs, and for a time, the Native Americans/First Nations people traveled between the US and Canada relatively freely. Even during the covid pandemic, Native Peoples were allowed to cross the border when non-Natives were not permitted to.

(c)2023

Many of the Haudenosaunee symbolism is the same – the flag, which is a copy of a Wampum belt, the tree of peace with the clan animals surrounding it, a condolence cane. Other items were not as familiar especially the artifacts from the more northern tribes, with their heavier and furrier parkas, snowshoes, sleds, and other unfamiliar (to me) artwork from the Inuit and the Mi’kmaq including musical instruments, Swinomish hats, kayaks, and canoes, and what we might call totem sculptures. Totem poles are typically from the Northwest Coast of both the US and Canada, including Alaska. The four large ones at the museum are memorial poles and are of the Nisga’a and Haida people of British Columbia. They are so large that they were put on display more than a decade after receiving them when the building was built around them.

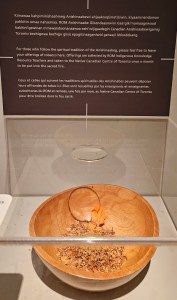

At the end of the exhibit, near the door is a clear box with a wooden bowl. Indigenous people who follow the tradition of offering tobacco for the sacred fire, a religious ritual followed by many nations, can leave their offerings of tobacco, and they are taken once a month to be burned in the sacred fire at the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto.

(c)2023

When I continued in my journey through the large exhibit, I was momentarily surprised to see a collection of Sitting Bull’s artifacts including his autograph (a replica), his ceremonial moccasins, his war shirt and war bonnet as well as other items belonging to him and photographs of him. I needed to remind myself that for a time, Sitting Bull crossed the border to get away from the US government soldiers who relentlessly pursued him. After the Battle of Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and his band refused to surrender to the military with other Lakota. This was when he headed north into Canada. He lived in exile in Saskatchewan for four years. He refused a pardon. As the herds of buffalo in Canada (as in the US) waned. His presence in the north led to tension between the two countries, and he eventually returned to the Black Hills and surrendered.

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota, and while he wasn’t known to have participated in the Ghost Dance which was making its way east from Nevada, he didn’t stop his people from the dance. He and his band lived on the Plains in isolation. He did not want to be on the reservation or on the agency lands. His death was entirely avoidable. In addition to killing Sitting Bull and some of his supporters, the Indian agency police also killed two horses. He was buried at the fort in North Dakota, but in 1953 he was moved to his birthplace where a monument was erected and still stands.