I’ve been really immersed in Native American spirituality and history. I have always been intrigued and felt kinship with Native American/First Nation people, being drawn to their stories, their history, and their lives since I was a child. It’s been something that has ebbed and flowed throughout my life, even with the insensitive and appropriated costumes of my childhood. I know better now, and I hope that in my past teaching in early childhood, I’ve lessened some of those stereotypical ideas as those children grow up and remember their experiences of the culture as best offered by an outsider and non-Native person.

I’ve recently mentioned attending a weekend retreat with Terry and Darlene Wildman and learning about the First Nations Version of the New Testament. It was enlightening and eye-opening, and I enjoyed the ceremonies we were invited to participate in. I’ve been a visitor and participant at the nearby St. Kateri Shrine when they’ve had those ceremonies open to the public.

I spent all of June reading the Daily Readings from the FNV New Testament; it really highlighted the beauty of Native American storytelling, and I felt that I was hearing some of these Scriptures for the first time and in a completely new way.

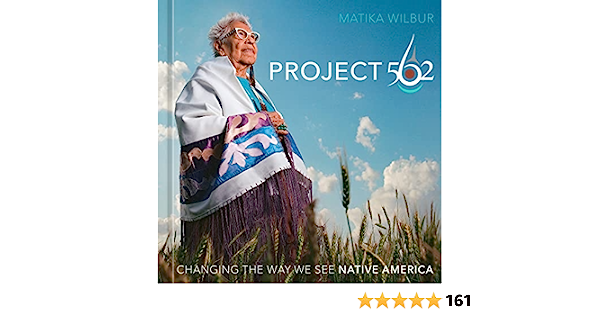

Which brings me to the most recent book that I’ve been reading: Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America by Matika Wilbur. I must say that I started the book in a naive headspace. I was looking forward to her interviews with modern Native people across Turtle Island (North America), hearing about how they keep their culture and religious rituals alive, and while I’m aware (more than the average person) of the history of the US’s forced removal, forced assimilation, and truly what can only be called genocide of the Native Americans, I was still surprised by so many things in this book that took me by surprise.

You can’t really talk about Native Americans in the US and Canada and not speak about colonization, residential schools, kidnapping, lying, theft, murder, and land confiscation. I honestly thought that most of that language was in the past. I’m a little embarrassed by that way of thinking. Especially since I consider myself open-minded, willing to listen and learn, and generally pat myself on the back at how much I have changed my own views. (That last sentence is said with a few grains of salt, and a self-awareness of how many White people think of themselves as they approach these issues.) What I discovered was that Indigenous peoples continue to live with colonization and the outcome of broken treaties and outright deception and fraud. The system was built on this deception and continues to reap the rewards while at the same time blaming Native Americans for their lack of education, housing, and anything else that was perpetuated by the US government and that the tribes continue to suffer through.

I was taken aback but needed to accept the references often in Project 562 to the United States as “the land currently known as the United States” or “now known as the United States.” It made me feel pointed to, and rightly so.

It is at this point that I should mention that as recently as June 2023, the Supreme Court ruled in Arizona v. Navajo Nation that (and I’m paraphrasing) while Native tribes have water rights in the Colorado River, there is no obligation for the US government to protect that water or even to provide access. This is what tribes are dealing with since the first European set foot on the land and began to push the Indigenous people westward when they weren’t outright murdering them.

Through the weekend in early June with Terry and Darlene, I learned a two-word phrase: Dominant Culture. I thought this was a much better descriptor than the white world or white culture, although we can’t let that get us off the hook for the supremacy still at large in this country.

Getting back to Wilbur’s Project 562, there were so many things that I learned, and things that reinforced and expanded on what I already knew, or thought I knew. I grew up learning a lot about the Native tribes. I loved, and still remember my 4th grade unit as a student on the Iroquois Nation. One of the things that always stuck with me, even as a young person, was their matrilineal society. It was the first time in history that I’d learned that women can run big things like a tribe. Being Jewish, which is also matrilineal, I was attracted to that as a parallel. The matrilineal aspect of the Iroquois made such an impression on me because other than my Dad and Uncles, our family’s older people were almost all women.

At the time, and up until I left for college, I had my mother, aunts, two grandmothers, and one great-grandmother alive with whom I could visit. I wish I were astute enough to have asked them the questions that I should have asked. I was able to ask my mother and my grandmother for a project I did for a social science class where I focused on the four generations of women on my mother’s side. I took my own children to visit the NY State Museum where they have a replica longhouse (only a cross-section), and it is still one of my favorite photos of my children. I recalled the pow-wows that my parents took us to for the Shinnecock tribe on eastern Long Island, but Wilbur’s book informed me that the Shinnecock people weren’t federally recognized until 2010. I must admit I was shocked by that late date.

In college, I took North American Indian as my anthropology course, which makes it sound like it’s ancient history; in my mind, anthropology and archaeology are the same discipline. Of course, I know the five tribes of the Iroquois, never mind that there are six. I know the Apache, Cherokee, Navajo, Hopi, and others. I did not know that Pueblo was the name of a tribe and not a place name. I did not know that Dakota was the name of a tribe. I learned that “Sioux” is not an Indian name, but a French one. I also did not know that the Cherokee, famously known for being mid-west and Plains Indians actually came from North Carolina. The same people that would include all the tribes in one monolith called “Indian” are the same people who would correct you if you suggested they were from the northeast when they were actually from the south. We cherish our regional differences and our multiculturality (if we’re Irish, Italian, or Hungarian, etc.) but then assume that Native people across an entire continent are exactly the same with the same songs, language, and ritual.

Matika Wilbur, who is a member of the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes of Washington state, went looking for the 562 recognized tribes and by the time she finished her project, there were 574. Not to mention the state recognized tribes, urban Indians, international communities (we have at least two in New York state), and Native peoples who are ignored because of arbitrary federal requirements to enroll in a tribe. I can’t speak as any authority on this, but I know to read and listen to Matika’s voice, and the voices of all the people she interviewed and photographed, hundreds of the thousands she met.

How many are there still lost to the ages?

I won’t spoil her story. Or the absolutely wonderful and spirit filled stories in the book. It’s really worth reading and after a short time away, re-reading.

After fifty years (in my case) of reading and learning and absorbing, I am still capable of learning something new, and in many cases, hard things that I don’t want to accept responsibility for, but need to acknowledge as a member of the dominant culture. Yes, I am a woman, I am Jewish, I have been a victim of discrimination, but I am still a member of the culture that has enormous privilege.

Reading this you may wonder if this is a book recommendation or an opinion piece on Native American rights. It’s both. It can be not easy to hold two thoughts in our heads, our hearts at the same time, but it is important to recognize and appreciate the variety of Native American/First Nations culture, religion, and history while also acknowledging that many of their communal difficulties came about by no fault of their own. Yes, there were language differences, cultural differences that defined things so differently that in some cases, the US representatives truly did have good intentions that went wrong, but they are in the exceedingly small minority. We need to acknowledge the intentional deceit; we need to make these wrongs right where we can. One way to start is to listen to the voices of the Native people. Listen to their priorities. Listen to their stories. Be a helper. Be an ally. Ask what needs to be done without coming along and taking over.

This book will introduce you to people who will teach you and make you want to learn more about them and the tribes and land they come from. The land is a part of them in a way that can be hard to understand. I had a similar feeling when I first set foot in Wales (as I’ve shared previously), and it can’t encompass the attachment to the land and to Creation that every Native person feels. They will inspire you; they will feed your spirit, they will show you their hardships and their blessings, both that they received and that they offered to others. You will laugh and feel kinship and that kinship will make you cry with some of their witness. Your heart will ache with pain and joy.

I went into reading this remarkable book as a fluffy, feel-good story to read as I settled in each night, but what I found was so much more multidimensional, more nuanced, more angry, and more hopeful than I could have imagined or expected. The description I give of the book is the description of its subject – Multidimensional, nuanced, angry, hopeful. I am in a better place having read these stories. I am a better person, and I am inspired, not only to do better with my social justice activity and my allyship, but to do better as a person, and to be forward thinking and not stop my dreams, my hopes. The book filled my spirit to overflowing, and I can only hope it stays with me long after I finish reading it.

How do I take what’s offered, what I’ve learned and use it respectfully and not co-opt it but honor it? I feel that so many of the thoughts and practices are universal or at least parallel practices in other cultures. The universality of circles and threes, the feminine, and calling on the ancestors. We don’t really have that in white or European culture like they do in Indigenous and Black/African and Celtic culture. We’re so afraid of the future and death that we’d rather ignore our honored dead than call on them as saints and wise ones to guide us or merely to witness and support us. Why is that?

Where is the line between honor and appropriation? How do we honor and not cross that line into offense or cultural blasphemy?

I don’t mean wear regalia or collect rocks or dirt from sacred land, but pray in the four directions, call on our ancestors with our needs and thanks, use herbs (like the mint from Archdruid Jeremiah locally and recently as well as the sacred plants used at the Kateri Shrine) or incense or fire, candles. Where does my intention, my practice become a blending of many practices like my Jewish and Catholic blendings?

I was twice privileged to hear Mohawk Elder, Tom Porter speak, the most recent time I was caught up in a supernatural incidence that I won’t soon forget. There is power in storytelling, in oral history, and in the listening. There is power in the first North American people, and we must find a way to make things right, if only beginning with the dishonored treaties that the Native people signed and accepted in good faith or at the end of a gun.

A conciliation (as Terry Wildman called it) is long overdue.